Review and Interview

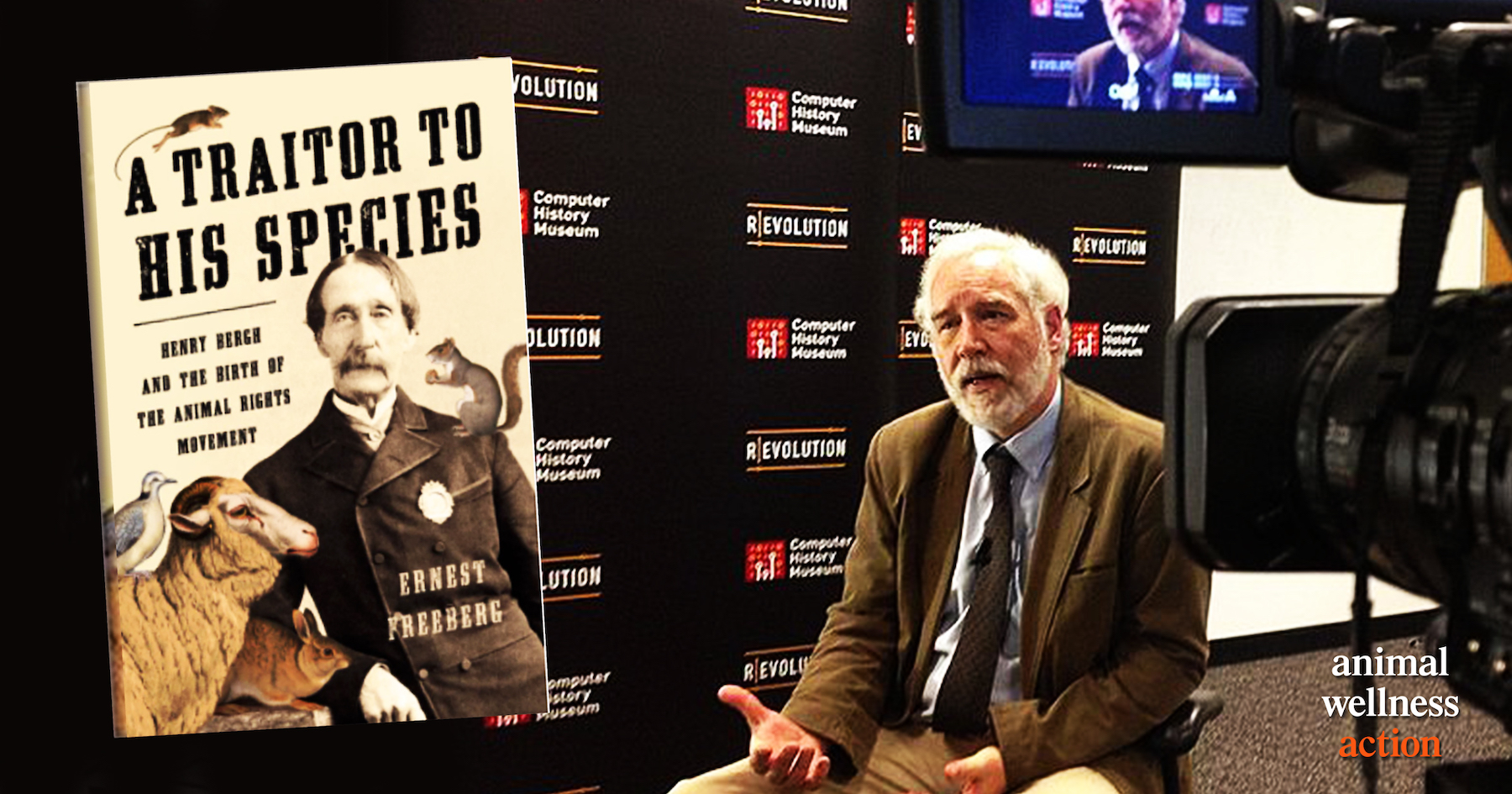

“A Traitor To His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement,” Ernest Freeburg, 2020

- Wayne Pacelle

With the embers of the Civil War still throwing off heat, and well into his 50s and having serving in diplomatic posts throughout Europe, including in St Petersburg where he had witnessed the abuse of horses on the street, Henry Bergh “brought the animal welfare movement to America,” according to Dr. Ernest Freeberg, professor of history at the University of Tennessee and author of a vivid and sweeping new biography of the ASPCA founder.

The founder of the first humane organization in the United States, Bergh was an apostle of kindness, but he delivered justice with an iron fist, taking on perpetrators of cruelty with a moral certainty and assertiveness that enraged his critics and earned him ridicule and scorn as well as admiration and a legion of followers. Tagged as “the Great Meddler” and called “a traitor to his species,” Bergh was best known, in an urbanizing America, for taking on the overworking and mistreatment of horses who shuttled people in carriages and trolleys and hauled crops, coal, ice, kegs, and other commodities and necessities.

“’[T]he streets of New York were his stage, in a performance that commanded the attention of admirers and critics alike, a role he felt God has written for him,” writes Freeberg in this richest of biographies of Bergh.

But his passion was not just fighting horse abuse, but every kind of cruelty. He challenged Kit Burns and other dogfighting organizers and disassembled cockfights and other blood pursuits. He was not a patrician taking aim only on the harsh behaviors of newly minted citizens in the cities. He was unsparing in targeting upper-class pursuits and business activities that left animals in a heap. After seeing the severe mistreatment of trolley horses, Bergh wrote to Cornelius Vanderbilt, the wealthiest New Yorker there was, and declared “I envy no man his gains obtained by the cruel sufferings of a dumb, speechless servant.”

He had legendary battles with P.T. Barnum and his emerging exploitation of wild animals at his American Museum. Barnum had assembled both human and wildlife “curiosities” and featured “modern wild beast shows,” including the feeding of live animals to snakes in front of recoiling and titillated patrons.

Bergh also took aim at the gentry for their live pigeon shoots in New York City, calling out their cruelty to the birds and demanding they lower their weapons. That work provoked a backlash among state legislators in Albany, prompting those who had empowered him to contend that he had now gone too far in his crusade. Ultimately though, many 19th-century proscriptions on live-pigeon shoots probably would not have gained momentum without his pleadings, as Bergh stirred other humanitarians of conscience to form their own anti-cruelty societies throughout the nation.

Though not a vegetarian at a time when there was some interest in that lifestyle, typically in utopian communities, he addressed every visible kind of harsh treatment, including turtle houses (where men took gustatory delight in consuming turtles who had been transported in horrifying conditions), cattle drives, and slaughterhouse abuses. This was an era before refrigeration and the cities brimmed with livestock transported from the hinterlands, kept cheek to jowl in city stockyards, and prodded into slaughterhouses where they met their end, with the bellowing and their other cries of distress in the “Meat Packing Districts” ringing in the ears of families prepping their evening fare.

Freeberg’s historical treatment of the horse flu epidemic of 1872 that raged throughout North America seems particularly timely for today’s readers. This zoonotic disease, which mainly kept itself to horses, sickened and killed so many animals that it ground to a halt the portage of crops from fields to markets, made it impossible for firefighters to haul water to buildings aflame, disrupted coal movements from rail stations to blast furnaces, and so much more. With horsepower fueling so many aspects of the late 19th-century American economy, the disease that afflicted these working animals, poorly understood as it was in the 19th century, was perhaps as disruptive to the functioning of society then as COVID-19 has been in 2020.

Freeberg has done stellar work in reminding us not only of the central place of animals in society, but of the pioneer who championed their plight and laid the groundwork for a serious-minded new legal and ethical framework for our treatment of Creation.

You can listen to Dr. Ernest Freeberg, about his new book, A Traitor to His Species: Henry Bergh and the Birth of the Animal Rights Movement, on our Animal Wellness podcast here.